Accused of triple murder with arsenic poisoning

Today, visitors to Lancaster Castle learn its fascinating penal history. Its courtrooms heard the cases of the Lancashire Witches, sentenced to death in 1612.

Displayed in the Crown Court dock is the branding iron used on offenders until 1811. But one of the strangest cases heard within the castle walls was that of Edith Bingham, tried for murder in 1911.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen William Bingham died aged 73, he had been resident caretaker at Lancaster Castle for 30 years. But on January 23, 1911, following a severe bout of vomiting and diarrhoea, his tenure ended. William’s death was attributed to old age and gastric catarrh.

Son James Bingham stepped into his father’s shoes, taking up residence that same month and employing his sister Margaret Bingham as housekeeper. Within a few days of taking this position she died on July 22, apparently of a cerebral growth preceded by severe gastric symptoms.

James then asked another sister, Edith Bingham, to be housekeeper, but soon recognised that she was not up to the job. He engaged an acquaintance, Mrs Cox Walker, to replace Edith, but before Mrs Walker could start, tragedy stuck a third time.

On August 12, 1911, James fell ill after eating a steak meal which Edith cooked. Local physician Dr Macintosh was called, but James got worse. Two days later, the doctor advised that a friend of James take in the patient. Next day, at the friend’s house, James died.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAn autopsy revealed arsenic in the corpse. Foul play was suspected and attention turned to Edith. She had, after all, cooked James’s meal before his illness. Arsenical weed killer used by the castle gardeners was discovered on the property.

William and Margaret Bingham’s deaths were remembered. Could Edith have been involved? These bodies were exhumed, and arsenic detected in each.

On September 14, 1911, coroner Neville Holden opened an inquest into James Bingham’s death at Lancaster Town Hall. Dr Macintosh stated that James’s violent vomiting had led the doctor to suspect poisoning and that arsenic was the cause of death.

Mr Roberts, assistant county analyst, testified that he had found in the deceased’s stomach and intestines traces of white arsenic, in total exceeding a fatal dose. He stated that only 10 drops of arsenic weed killer like that used at the castle could kill.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPolice Inspector Whitefield stated that when he had arrested Edith Bingham, she denied the charge, saying that the weed killer was only used on the castle grounds by William and James. However, at that point, the inspector had not even mentioned weed killer to her.

Two weeks after the inquest opened, Edith Bingham was charged with the murders of her family members and remanded in custody.

When the inquest resumed, Mr Seward Pierce, for the Crown, focused on James Bingham’s death. Mr Wingate Saul, defending, argued that Edith had no motive to kill James because she would lose her home if he died. On the inquest jury returning a murder verdict, Edith was sent for trial at the next Lancaster Assizes, held in the grounds of the castle where the deaths occurred.

She was tried for the murders of her father, sister and brother. The evidence seemed overwhelming.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the trial which opened on October 27, 1911, Mr Langdon K C led the prosecution. Edith’s surviving brother William testified to ill feeling between her and her brother James because Edith overspent, neglected her duties, and went out too much.

Medical evidence was given by Dr McIntosh who attended James during his fatal illness. County analyst Mr Roberts testified that the wallpaper and the distemper in the Bingham’s accommodation had been tested for arsenic and none detected. A cleaner stated that she had seen Edith cook the suspect steak. Although Edith usually shared meals with James, that time she declined.

Edith did not testify, and the defence called no witnesses of their own. Mr Wingate Saul reminded the court that the defence did not have to show that Edith had not administered poison to James Bingham.

It was up to the prosecution to prove that she had. Evidence seemed to tell heavily against Edith.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYet all could be seen in a different light. The idea that Edith had killed James because he had dismissed her as housekeeper, was barely plausible. Edith had access to arsenic, but then so did household members and other staff.

She had opportunity to administer poison. Indeed, she had served the suspected steak. However, the maid who testified to this saw nothing suspicious when Edith prepared and cooked the meat.

Following the exhumation of the bodies of William and Margaret Bingham, it seemed that they could have died from arsenic poisoning. But William had been in the grave for eight months and Margaret for a month, and arsenic could have entered the corpses from other sources, such as grave earth.

But if James Bingham and any other family members died ‘innocently’ from arsenic poisoning, where did it come from? Perhaps it was arsenical weed killer used by the castle gardeners. If handled casually, it could have poisoned one or more family members accidentally.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

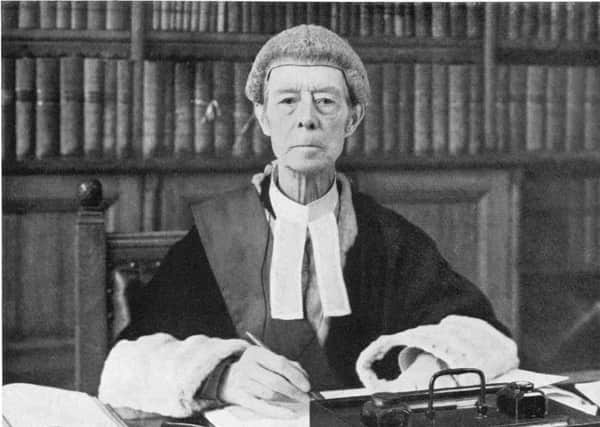

Hide AdSumming up, the judge Mr Justice Avory told the jury that they must be convinced that Edith had given arsenic deliberately and maliciously to James before they could find her guilty. It was difficult to see how Edith could have poisoned Margaret without poisoning other members of the household. Also, there was no evidence that she had administered arsenic to her father. Accordingly, only 20 minutes after retiring, the jury returned with a verdict of ‘not guilty’.

Edith Bingham walked free from the court leaving behind her an enduring mystery.

l Dr Michael Farrell is the author of Criminology of Homicidal Poisoning.