What next? Lancaster's slave trade past in the spotlight again as calls are made to re-name streets and create a new memorial

and live on Freeview channel 276

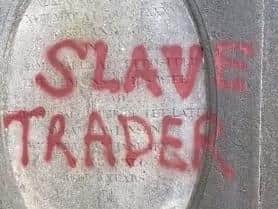

This week, a family monument in the grounds of Lancaster Priory Church was daubed with the words "slave trader".

The graffiti is accurate - the Rawlinson family was involved in the importation of mahogany and in the slave trade during the 18th Century - making vast sums of money in the process.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

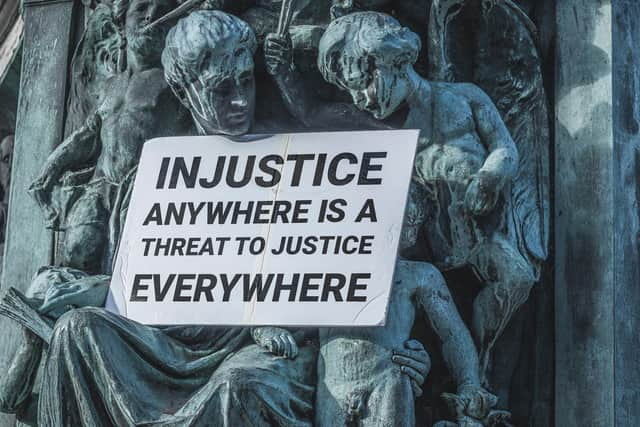

Hide AdThe Black Lives Matters (BLM) protests in Lancaster and across the world - sparked by the death of George Floyd in the US but fuelled by countless other incidents of racism and oppression over centuries - have resulted in a chain of events that has already seen statues removed - one thrown into the sea - in other English towns and cities.

Campaigners are now calling for many others to be removed.

Calls have also been made to Lancaster City Council to re-name streets such as Lindow Square, while many people feel the education system needs to better reflect the country's colonial past, and the way in which this changed the world, and which is now making history again.

The term "decolonisation" attempts to describe how this could be untangled.

A series of Tweets by Lancaster University sociologist Imogen Tyler documenting Lancaster's huge slave trade connections went viral, while Lancaster City Council has said that the events provide "the catalyst for a wider conversation about Lancaster’s slave trade legacy and the way those who were directly involved have been commemorated."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Rev Chris Newlands, Vicar of Lancaster, made a statement in front of the Rawlinson memorial this week, after it was graffiti'd with the words "slave trader".

He said that while he does not endorse the act, he can understand the sentiment behind it.

He was due to retire in September, but told the Lancaster Guardian that he "cannot retire in a crisis" and would remain in his post for now.

He described the way in which vast sums of money were made during the slave trade as an "abomination" and announced potential plans for a new memorial to commemorate the "countless" slaves that were seen as possessions, often abused and killed, many right here in the Lancaster area.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said: "The slave trade is, to our deep shame and lasting regret, a part of the history of this city.

"And our history is one thing that we cannot change, much as we would like to.

"What we can, and must change in our present – is the appalling inequality in our society which does not treat all people as equal.

"The Black Lives Matter protests in our own country as well as throughout the USA and other nations, has made that important point very clearly.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"The memorial is above the vault in which are buried the members of the Rawlinson family, whose vast fortunes placed them among the wealthiest of Lancaster’s citizens at the time.

"This memorial is a clear statement of their wealth and status.

"However that money came from the slave trade which, though accepted in their own day, is now seen as an evil which still needs to be expunged from the world.

"In England, a law was passed in 1807 to abolish the slave trade.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"We commemorated its bicentenary some time ago – but as we did, we acknowledged that there is still slavery in the world, where people are exploited, abused and even killed because of their ethnicity, and that is why we absolutely need to support the Black Lives Matter Protest.

"I am not endorsing this vandalism, though I do understand the righteous anger which made it happen.

"People are more important than monuments, let me be clear about that.

"This monument is a part of the history of our city, whether we like it or not.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"And this graffiti is now also a part of that history, representing a moment in time when anger over the death of a black man’s murder by a white policeman in the United States, spread across the world.

"I hope this moment in time makes a difference in every nation, and that all people can stand up and say that Black Lives Matter.

"BAME people and those of us who stand up to be counted as their allies cannot change our history, but we can make our present a better place.

"We are beginning to look at the possibility of having a memorial in the Churchyard to the countless slaves who were seen as possessions and not as even human, and who bore unimaginable pain and abuse, and even death to secure profit for those who made vast wealth from their suffering.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"Perhaps that would go some way to being a necessary corrective to trophy-memorials such as this."

Lancaster's slave trade history is well documented, and there have been many events, exhibitions and talks over the years to bring the matter to light.

There are also many examples of modern day slavery happening right here in the city and wider county over recent years.

In a letter to Lancaster City Council, Geraldine Onek, who the Lancaster Guardian spoke to last week about her own experiences of racism in Lancaster, said: "The recent wave of anti-racism protests around the world, in support of black lives, has been an encouraging and welcome sign that communities are ready and willing to address the racial injustices that permeate every aspect of British society.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"I would like to know, what steps Lancaster City Council will take, to ensure that the atrocities committed here, in our district are brought to light?

"What steps will they take to ensure that the victims of Lindow, Gillow, Bond, Barber and others are honoured in the same way those men have been honoured?

"What commitment will Lancaster City Council make to ensure that present-day racial inequality in Lancaster is identified and addressed?"

In response to the campaign requesting the renaming of streets linked to those involved in the slave trade, the council released the following statement: “The city council’s decision to light the Ashton Memorial purple over the weekend was a strong symbol of our solidarity with all those who are protesting against prejudice, injustice and discrimination in all their forms.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"It also provides the catalyst for a wider conversation about Lancaster’s slave trade legacy and the way those who were directly involved have been commemorated.

“We welcome the opportunity that this campaign has provided in creating a space for those discussions to take place.

"This will allow us to develop a deeper understanding and reflection of the issues, the views of our communities, and how we can work together to develop a response."

Prof Imogen Tyler, a sociologist at Lancaster University, recently published a book called Stigma - The Machinery of Inequality.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe said her daughter attending the Black Lives Matters protest in Dalton Square prompted her to consider the location of the protest, and how some of the buildings in the square were connected to the slave trade.

She was able to draw information from her book, in the series of Tweets included below.

She said: "She sent me some photos back, and I was really struck by the fact that Dalton Square itself, and some of the houses, and those that lived there, were connected to slavery and plantation ownership overseas."

Today, she said that new research has revealed how "the wealth derived from slavery and slave ownership in Lancaster directly shaped the establishment of a new class of powerful elites in Britain."

She Tweeted:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad#BlackLivesMatter in Lancaster, UK. A brief thread on making visible Lancaster's local & global histories of Slavery & Plantation Labour, legacies of colonial capitalist extraction, & racialised violence which shape the (failed) neoliberal market economies of the present.

In the 18th century, Lancaster was heavily involved in the Atlantic slave-trade. It was the fourth largest slave-trading port in England, developing its River Lune Quay Side Port. http://collections.lancsmuseums.gov.uk/narratives/narrative.php?irn=43

Lancaster merchants developed commercial networks in the West-Indies & Americas. Importing slave-produced goods, mahogany, sugar, dyes, spices, coffee & rum, & later cotton for Lancashire’s mills, from plantations, & exporting fine furniture, gunpowder, woollen & cotton goods.

Young men from Lancaster families worked as agents and factors across the West-Indies, and Lancaster families became wealthy plantation and slave owners, wealth inherited through generations. (see historian Melinda Elder)

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLancaster's most famous son, the anatomist & palaeontologist Sir Richard Owen, who coined the word dinosaur & founded the Natural History Museum, was the son of a Lancaster based West Indies Merchant (died in St Barts) who was almost certainly involved in slavery in some form

In 1754, a Lancaster born slaver called Miles Barber established one of the most significant commercial slaving hubs in the history of British involvement in the Atlantic slave trade. (see Bruce Mouser https://doi.org/10.3406/outre.1996.3483…)

This place of horror was called ‘Factory Island’, and was situated on one of the Iles de Los Island group off the African coast of Guinea-- just north of the Sierra Leone River. (see also http://slaveryandremembrance.org/articles/article/?id=A0140…)

Over the course of the following decades Barber developed and managed an estimated 11 slave factories and barracoons along the West African coast. By 1776 Barber was being described by his contemporaries as the owner of ‘the greatest Guinea House in Europe’. (see Elder in below)

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs Eric Williams details in Capitalism and Slavery (1944), slave traders dominated local political life in towns like Lancaster ‘as aldermen, mayors and councillors’, and some invested their inherited fortunes in the development of local mills and businesses.

by ‘1750 there was hardly a trading or a manufacturing town in England which was not in some way connected with the triangular or direct colonial trade. The profits obtained provided ... that accumulation of capital in England which financed the Industrial Revolution.’

The first cotton mills in the Lancaster district were established in a village called Caton in 1783, by Thomas Hodgson (1738–1817). Thomas & his brother John worked as slave traders for over 30yrs. Between 1763-1791 they were involved in the capture & sale of circa 14,000 people

Thomas began his slaving career working for the Lancaster born slaver Miles Barber, indeed records suggest that the Hodgson brothers took over the running of “Factory Island” off the African coast from Barber in 1793, a decade after they opened their first Lancashire cotton mill

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Hodgson cotton mills in Caton specialised in the exploitation of pauper child labourers, transporting orphans from urban centres across England, primarily from Liverpool but also from London, to work in their mills as forced apprentice labour. (See local historian Huddleston)

During the same period, John Bond (1778 – 1856) who would twice be appointed as Major of the town, inherited several plantations and over 700 enslaved people in (then) British Guiana & Grenada from his slave trading uncle Thomas Bond.

His inheritance included a cotton plantation in Guiana (Guyana) Lancaster. This other Lancaster, a cotton plantation, was visited in the mid-C18th by an English physician, Dr George Pinckard, who described it as ‘distinguished’ by ‘the inhuman treatment of the slaves’.

Lancaster Town Hall sits in Dalton Square, scene of recent #BlackLivesMatter solidarity events, which contains grand Georgian houses. 1 Dalton Sq. was home to aforementioned plantation & slave-owner John Bond, who lived off the profits from the "other Lancaster" in Guiana

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn Bond became a multi-millionaire overnight, when the British Government legislated that taxpayers would compensate a wealthy group of aristocrats, landowners and middle-class inheritors, for the loss of their human property. See The Slavery Abolition Act of 1833

Details of the huge windfall (approximately £2 million pounds) received by John Bond, the compensation for freedom of slaves in British Guinea, as part of a £17 billion pounds package of compensation paid to former slave-owners, can be tracked at https://ucl.ac.uk/lbs/

John Bond spent a lot of his fortune employing the esteemed Lancaster furniture company Gillows to furnish his Dalton Square House & other properties - Gillows was another Lancaster business also knee deep in histories of slavery & plantation blood.

Founded by Robert Gillow in 1728, this acclaimed manufacturer pioneered the use of mahogany from the West Indies in the crafting of expensive furniture for British & colonial elites. Gillow was also a significant Atlantic slaver who financed a number of Lancaster slave ships.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRobert Gillow & his partners took care to conceal their connections to the Slave Trade, but examination of their books suggests that between 1754-1765 three quarters of the ships financed by Gillow’s were slave trading vessels.

& at least 40% of Gillow's profits in the mid C18th came from profits made in the selling of human beings, and the rest was supported by slave-labour (mahogany, Rum, Sugar and more).

Not for nothing is Lancaster University Student Union Nightclub called 'the Sugar House' - a former sugar processing & storage site in Sugar House Alley opposite Green Ayre on the banks of the Lune River, the place slave ships & other trans-Atlantic vessels where made & launched.

After his tax-payer windfall, Bond was one of Gillow’s biggest clients & his son Edward later became a partner in the firm. The fine houses in Lancaster & their mahogany cladded interiors conceal universes of barbarity, terror & suffering. The poet Dorothea Smartt writes on this:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe histories of slavery, plantation & industrial exploitation on which Lancaster was built have only been partially researched, we have a slave memorial on the Quay, & important work by historians such as Alan Rice & artists such as

If you are interested in decolonizing local histories please do let me know below. I am continuing to work on my "Decolonizing Lancaster" research, including through collaborations with historians, artists & others in the local community.

As Lubaina Himid writes Lancaster is 'a city in which traders became Abolitionists & in which Quakers owned slave ships. There are beautiful buildings designed by men involved in horrible deeds. Behind doors ... hidden histories of almost invisible African people' (in Rice below)

Long after the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade (1807) & long after the profits had been collected from the abolition of slavery in the British empire (1833), Lancaster & Lancastrians continued to profit from historical ties to slavery & plantation economies.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor example, Lancaster's C19th century industrial heyday of ‘Lino Kings’ was underpinned by slavery "windfalls" & by cotton imported from plantations in the Americas, a web of connections which can be traced through industrial & economic histories, & family inheritances.

On this interconnedness see Himid’s http://cotton.com project, which brings the words of mill-workers & plantation workers into dialogue through the medium of cotton & words, words collected on the plantation & in the factory in the mid-19th century.