Make hay while the sun shines was vital work on Wray village farms

and live on Freeview channel 276

In favourable weather haymaking would begin in the middle of June on low-lying village farms.

In the Dales it began slightly later, towards the middle of July.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

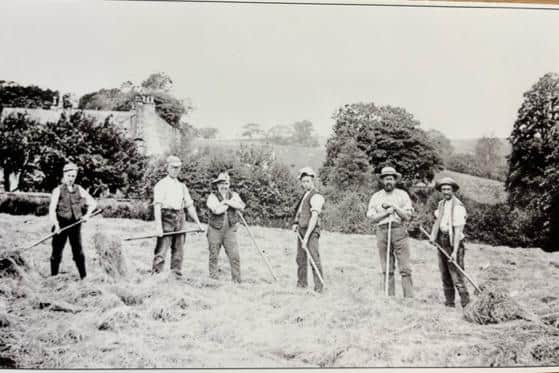

Hide AdPrior to 1900, most grass would be cut by gangs of scythe mowers, moving from farm to farm.

The mowers used old English pattern scythes, which consisted of a straight long shaft and a blade approximately five feet in length.

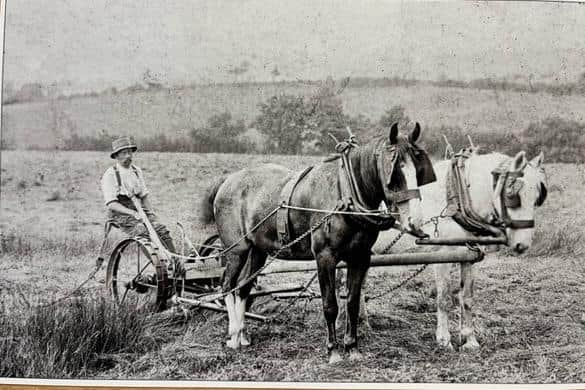

Horse-drawn mowing machines appear to have been in use from the late nineteenth century onwards.

A local joiner and wheelwright account book lists repairs to mowing machines as early as 1865.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe introduction of this new technology did not, however, bring an immediate end to traditional methods, as gangs of scythe mowers were still working as late as 1900.

The next stage in the process was turning the rows of cut grass left by the scythe or mowing machine, known as ‘swathes’.

This was either done by hand, using a hay rake, or by machine, using a horse-drawn swathe turner or side delivery rake.

Turning the swathes enabled the underside to dry as well as exposing the ground to the sun.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter turning the swathes, the next day’s job was to scale out the grass using hay forks or a horse-drawn scaling machine.

The following day the hay would be turned into rows, known as ‘windrows’.

If the weather was very hot, the turnings would just need to be pulled together into large rows called ‘plats’.

During warm weather, it would take around four days to turn grass into hay.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, in wet summers, haymaking was a difficult task and the hay could be out in the field for several weeks.

If rain was likely the hay had to be put into rows then made into ‘foot-cocks’ or larger ‘jocky-cocks’.

These were conical in shape so rainwater ran off, resulting in both hay and ground drying out quicker, once the sun returned.

When the threat of rain passed, the hay had to be scaled out again, following the procedure described above.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe summer of 1946 is remembered by several local farmers as being a very poor year for haymaking.

There was one fine week at the beginning of July but after this the weather deteriorated.

Some local farms did not get their hay into barns until October.

Such weather often resulted in poor quality hay. When this happened, treacle was added to make it more palatable to cattle.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdVarious methods were used to transport hay from the fields to barns or haystacks.

These included horse and cart, the sweeping method or using a pike bogie.

Horse and cart was the most common.

The loader was one of the most important jobs in this process.

The hay was put into plats then forked up to the loader who was stood in the cart.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe loader would wrap the hay into a ball then press it into its allocated place in the cart.

Carts would be fitted with shelving around the outside to increase their size.

A skilled loader was held in high regard among local farmers as they could maximise the carrying capacity of the cart.

When the cart was loaded, ropes were used to secure the hay in place.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe loader would then remove any loose hay with a rake before horses pulled the load to the hay-barn or stack.

Although the traditional horse and cart method was the most popular, quicker alternatives were available.

The sweeping method used two horses working either side of a plat to pull a box-like device along which collected the hay.

Once full, it was pulled to the barn where the hay was tipped out and forked up through an opening.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen all the hay was harvested, the field would be raked to collect any that remained on the ground.

In earlier times this would be done by hand, though later on horse-drawn rakes were used.

An improvement on the hand rake was the rover: a hand-pulled rake about four feet wide with metal teeth.

Once the hay arrived at the barn, the horse would back the cart through the main doors and unload the hay either side of the cart.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOtherwise, the hay entered the barn through a small door high up on the barn wall.

Once inside, the hay was spread around and trodden down, a process known as ‘mewing’.

Following the introduction of tractors, haymaking changed dramatically.

The tractor-pulled baling machine, introduced in the 1950s, picked up the hay from the plats which made the loading of carts, forking up and sweeping redundant.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, despite the technological advances, haymaking was still dependent on good weather.

Prior to around 1960, most local farms employed migrant workers from Ireland who would come to England for the summer.

After World War Two, the average rate of pay for an Irish hay-time worker was £40 a month, rising to £53 by 1953.

There were no set hours; the working day would last until the job was complete.

Hay-time also offered locals the chance of an extra income.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMen and boys would go to local farms in the evenings and at weekends to help.

Indeed, the long school summer holidays were originally designed so that schoolchildren could help with haymaking and the harvest.

Today the making of silage for winter feed has mostly superseded hay-making.

Unlike hay, making silage is less reliant on the weather.

Huge machines cut and harvest the grass into large plastic-covered bales that are a common sight in fields throughout the district today.